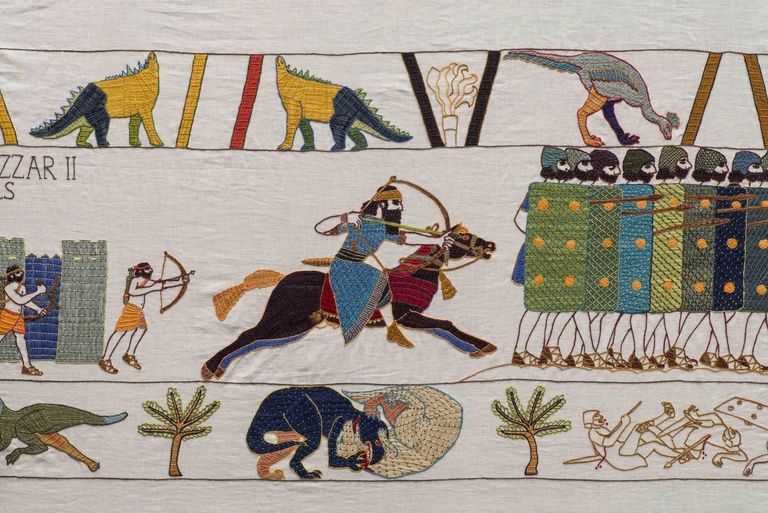

Sandra M. Sawatzky (Winnipeg, Manitoba, 1957–Calgary, Alberta, present), Mesopotamian archer and warriors, from The Black Gold Tapestry, 2008–2017. Silk and wool threads on flax linen cloth. Courtesy of the artist.

Breadcrumb

The Black Gold Tapestry

On View February 3, 2026 – June 14, 2026

After a museum visit revived Sandra Sawatzky’s interest in embroidery in 2007, she conceived of The Black Gold Tapestry, which she describes as a “film on cloth” devoted to the cultural history of fossil fuels. Sawatzky, who resides in Calgary (the oil capital of Canada), hand embroidered this 220-foot-long tableau over the course of nine years. To tackle the imposing subject, she conducted extensive research: “Geology, paleontology, chemistry, mining, automobiles, aeroplanes, rockets, drilling, distillation, weapons, whaling child labour, combustion engines, robber barons, textile mills, the world wars, royal jewels, and the colour purple, just to name a few, that all inform this history of oil.”

Sawatzky, who has worked in fashion and film, began by making drawings in a sketchbook. She then traced and arranged these elements in a paper cartoon, which guided her design on the linen cloth. Formally, The Black Gold Tapestry takes cues from the Bayeux Tapestry, an eleventh-century textile frieze that recounts the conquest of England by the Duke of Normandy. This medieval embroidery (like Sawatzky’s, it is technically not a tapestry) consists of fifty-eight captioned scenes depicting the Norman invasion, but the incidental details about everyday life are what make it especially noteworthy. Sawatzky borrowed the compositional logic of the Bayeux tapestry, organizing her design into three pictorial registers. In her narrative, this layered approach also evokes archaeological principles of stratigraphy; throughout, the hand-dyed wool/silk threads match colors with specific periods and places.

Sawatzky’s undertaking also recalls the serial modernism of Jacob Lawrence’s (1917–2000) sixty-panel Migration Series, which envisions the early twentieth-century diaspora of African American people from the southern United States. In the twenty-first century, immersive art experiences have become synonymous with multimedia technologies, but The Black Gold Tapestry challenges that association. Sawatzky resets expectations of instantaneity with her methodical, manual labor and the correspondingly measured experience of viewing her artwork. She reminds us of the gendered and communal roots of handicraft in Western societies at a moment when community and cooperation are being undermined, and facts related to resource extraction and climate change have become politicized. As Rozsika Parker argued in her foundational text The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine, handicraft like embroidery “has been the means of educating women into the feminine . . . but it has also provided a weapon of resistance to the constraints of femininity.”

The phrase “black gold” first appeared in connection with the oil industry in the early twentieth-century, indicating oil’s relative rarity and value. In the final vignette of The Black Gold Tapestry, Sawatzky reflects on the tensions between petrochemical and renewable energy industries a century later by positioning the two-headed figure Janus, Roman god of transitions, between wind turbines and an oil derrick.

Details from The Black Gold Tapestry, 2008–2017, Silk and wool threads on flax linen cloth. Courtesy of the artist.

Photos: Don Lee, Banff Centre, Alberta, Canada.