Breadcrumb

Director Lessing Reflects on Oliver Lee Jackson

One of the most exciting aspects of working at the Stanley Museum of Art has been discovering the incredible legacy of the University of Iowa’s studio art program. Home to the first MFA program in the world, Iowa’s School of Art and Art History has, for over a century, produced groundbreaking artists who have altered the course of art history. So, I suppose I shouldn’t have been surprised when my phone buzzed on an early spring evening last year, and I looked down to see a text from an old friend--a curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. “I’m at dinner with Oliver Lee Jackson,” he wrote. “Are you aware that he’s an Iowa MFA?” I was not aware, although I was certainly familiar with Jackson’s beautiful work. How could I not be? He had just had a major exhibition at the St. Louis Art Museum that followed on the heels of an equally triumphant one-man show at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. “If we were in Japan, Oliver Lee Jackson would be what they call a living national treasure,” commented the National Gallery’s senior curator, Harry Cooper, in 2019. And he is right. In painting after painting and in sculptures, prints, and drawings too, Jackson has broken new ground: combining figuration and abstraction in innovative ways, deploying color and space like no painter since Joan Mitchell, unleashing stunning, virtuoso improvisations inspired by jazz, and exulting in the joy of making. Jackson was an early member of St. Louis’s Black Artists Group, which—as the jazz musician and artist Oliver Lake has noted—served as a crucial catalyst for the international Black Artists Movement of the 1960s and ‘70s. “The members of BAG… fused ideas of artistic modernism with the local experience of blacks, Afrocentric ways of viewing art, and traditional forms of blues, jazz and narrative expression with social activism and a communal focus.” Through his participation in the Black Artists Group, Jackson learned to weave elements of music, dance, poetry, and performance into his art. By celebrating Black culture and by training other Black artists, he contributed in pivotal ways to the Black Power movement.

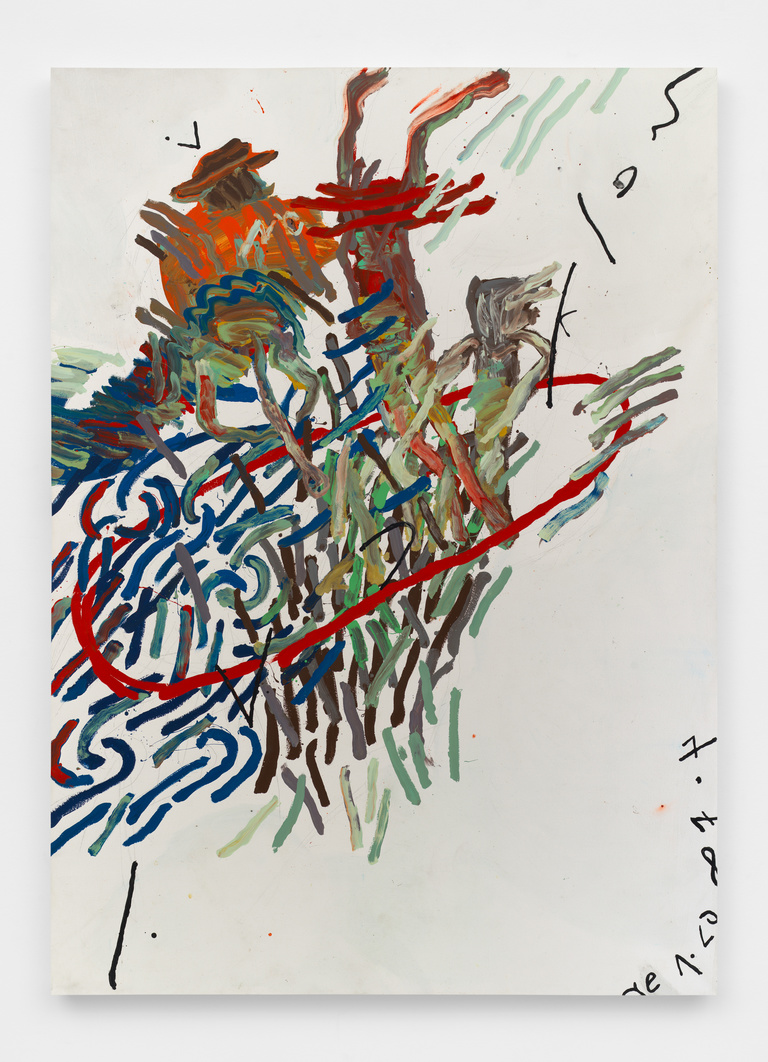

“I am so happy to know this!” I texted back to my friend. “Please tell Mr. Jackson that I want to meet him soon.” The next day, I contacted the artist through his website and invited him to Iowa for a week-long residency. I also began making inquiries with his galleries about a significant purchase for the Stanley. A gift from an Iowa family made it possible for us to acquire a large and gorgeously painted 1979 diptych (two paired paintings) by Jackson just in time to install them in our inaugural exhibition, Homecoming. When the Stanley reopened its doors fourteen years after the devastating Iowa River flood, Oliver Lee Jackson’s work hung proudly in our galleries, adjacent to works by Joan Mitchell, Philip Guston, Alma Thomas, and Robert Motherwell. His diptych will remain on view until at least 2025. “Both paintings pulse with tension between figure and ground,” wrote the Stanley’s visiting senior curator of modern and contemporary art, Diana Tuite. “Each canvas seems to exert a centripetal force, propelling a swarm of hatched marks and loose forms into circular shapes at center.” Standing in front of these powerful paintings, I imagine the jazz that played as Jackson painted them and the dance-like movements that allowed him to create these sweeping, curving, and slashing brushstrokes. I find in the swirls of paint the half-abstract “paint people” that--according to Jackson, who was a student of the Iowa artist Byron Burford--anchor our perceptions. I am in awe, and very proud to work at the university that helped to train this national treasure.

Painting (4.78-I) and Painting (4.78-II)

1978

Oil-based enamel on cotton canvas

Museum purchase, 2022.21 and 2022.22